THE DISAPEARANCE OF THE XI LEGION |

Brought to you by Albawest |

|

Pict Weapons |

A Roman writer tells of the weapons that the Caledonians used. 'Their arms are a shield and a short spear, in the upper part whereof is an apple of brass, that, while it is shaken, it may terrify the enemies with the sound, they have likewise daggers. They are able to bear hunger, cold, and all afflictions.' A measure of how troublesome the Caledonians were to the Romans is shown by the fact that one of the largest and most complex military forts in the Roman Empire was built at Ardoch in modern Perth in Scotland, and that within 10 years the Romans would be driven out of Caledonia for the first time. |

Disappearance Of The IX Legion |

|

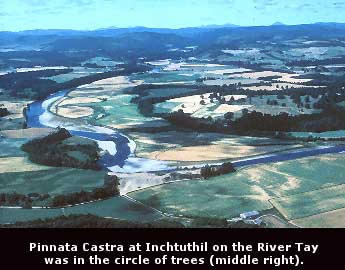

In the territory ( in modern Perthshire ), of a Pict tribe the Romans called the Vacomagi just below ( according to Ptolemy ), the territory of the Calidonii tribe, the IX Legion built a 53 acre 'great fortified camp' at Inchtuthil on the river Tay, called Pinnata Castra ( Fortress on the Wing ). The word for wing that the Romans used in the name of the fort, is also used for the wing or feathers of a bird and it seems to be a reference to the wing of the Roman eagle - symbol of the empire. Fort on the wing [ fringe or edge ] of the empire. In modern terms the Romans perhaps felt themselves to be living on the edge, in more ways than one - especially as the fort was near the edge of their main enemy the Calidonii. The fort was defended by a turf rampart 13 feet / 4 meters thick, and at the front by a stone wall 5 feet / 1.5 meters thick, with a ditch 20 feet / 6 meters wide and 6½ feet / 2 meters deep. |

Although the Romans controlled large tracts of land they just couldn't conquer the country. In order to gain a wider control Agricola split his force into three groups. 'When Agricola learnt that the enemy's attack would be made with more than one army. Fearing that their superior numbers and their knowledge of the country might enable them to hem him in, he too [ like the Picts ] distributed his forces into three divisions, and so advanced.' Leading the Romans to believe that the Pict army had split into three divisions was a brilliant piece of Pict false information that had the desired effect of getting the Romans to split their forces - with dire results. It appears to have been the only mistake Agricola made during the invasion. When Agricola split his force into three, the IX [ Ninth ] Legion - who seem to have been especially hated by the Picts perhaps because of some heinous act of brutality - became the Picts main target. There is some dispute as to what camp the IX were in when attacked, some believe Pinnata Castra ( which I favour ), but the prevailing view at present seems to be that it was their camp at Lochore in modern Fife. My argument for Pinnata Castra is that it was deeper into Pict territory, near the border of the Calidonii, but within reinforcing distance of the other camps particularly the large camp at Ardoch and so could be reached by Agricola relatively quickly, whereas Lochore was an earlier camp further south - not far enough into the main Pict territory and only about 35 miles from the legions winter quarters. It does not fit Tacitus' statement that Agricola distributed his forces into three divisions, and so advanced i.e. all three divisions advanced. |

View a map where the location of many of the sites mentioned are shown CALEDONIAN MAP |

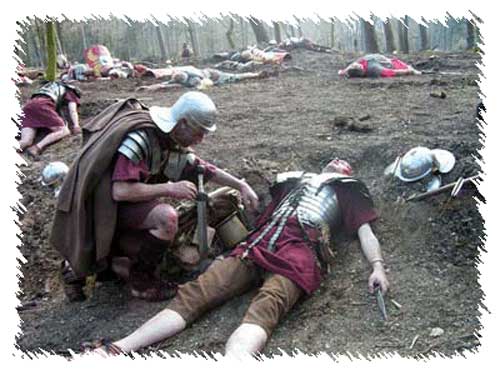

Tacitus had written earlier that 'not a single fort established by Agricola was either stormed by the enemy or abandoned by capitulation or flight'. This was about to change. The Caledonians carried out a daring attack in the dead of night on the fortress of the sleeping Ninth Legion - it was payback time ! Tacitus doesn't admit that the Roman intelligence was wrong but that the Picts, 'suddenly changed their plan, and with their whole force attacked by night the ninth Legion.' They first set bodies of troops at key positions to intercept any fleeing Legionnaires and then advance units overpowered the guards. In Tacitus words, 'Cutting down the sentries, who were asleep or panic-stricken, they broke into the camp.' The statement that guards were asleep appears to be another spin on the truth by Tacitus. It is very unlikely that any of the guards were asleep because they were inspected at regular intervals and also because the penalty for being asleep on guard-duty was death. It seems the advance attackers managed to open the main gates allowing the waiting united Pict army to pour into the camp in their thousands, there may have been as many as 20,000 or 30,000 of them. Tacitus says, 'the battle was raging within the camp itself.' No doubt the 5,000 Romans sought to quickly organised fighting units; probably numbers of men without officers banded together for their own safety and attempted to make a stand, but many groups of awakening disorientated legionnaires, separated from their unit and in mortal fear, were thrown into a confused terrified panic in which they could see only one course of action - escape from the confined death trap of the fort. Most of them wouldn't even have had time to put on their armour. A messenger managed to get through the Pict line and Agricola eventually came to the rescue with cavalry units just in time to save the remnants of the IX; if not for his actions the Legion might have become extinct at that point. The fierce fight with the cavalry units at the gate of the fort was probably called off by the Pict leaders because day was dawning and because Roman infantry units were on route to relieve the IX. Tacitus is ashamedly silent about the IX' casualty figures, which must have been several thousand at least. The Romans couldn't simply reinforce the IX from other units, probably because more than half the Legion had been lost. They had to bring in a replacement Legion, pull the remnants of the IX out of Caledonia, re-form the whole Legion and repopulated it with new recruits and officers. Given the circumstances of the attack and the major task of rebuilding the Ninth, the casualties could even have been as high as two out of every three legionnaires. As the depleted thin ranks of the Ninth assembled for roll call the next morning it must have been a sad, depressing event that deflated Roman pride as name after name was called - and no-one answered. It is little wonder that Tacitus recorded that Pict attacks like this one 'spread terror' among the Roman Legions: 'the native tribes assailed the forts' ( Note that the word 'forts' is plural ): 'and spread terror by acting on the offensive.' Excavations between 1952-65 revealed that within 4 years (about AD 85 ) of the attack, the Romans - afraid that the Caledonians would melt down any iron they left behind and hammer them into weapons - buried in a 12 foot / 3.5 meter pit, a hoard of over 875,000 hand-made iron nails, ranging in length from 2 inches / 5cm up to 16 inches / 40.5 cm, with a combined weight of 7 tonnes. They then tightly filled up the drains and sewers with gravel, set fire to Pinnata Castra and abandoned the whole area. The Emperor of Rome marshalled a renewed Ninth Legion and after the recall of Agricola back to Rome, he sent them for a few years of training and campaigning to battle harden them, (they were known as the 'Hispana' because they helped conquer Spain for the Roman Empire). The Emperor then sent them to teach the Caledonians a lesson about the power of Rome. The new IX Hispana Legion proudly marched north - and simply disappeared. Not one trace has ever been found of them or any of their equipment. Some historians have claimed that the IX was pulled out of Caledonia but the Romans forgot to record that fact. However, the Romans did not loose a Legion in the paperwork; something terrible seems to have happened to the IX, it is as if they just ceased to exist. Perhaps they suffered the ultimate shame - the Picts annihilated the IX and captured the Legion's Standard and so the disgraced remnants of the Legion were disbanded, and all records of its fate were erased. Roman policy was not to publicly record the fate of legions that had been disgraced or annihilated in battle. These disasters were looked on by the people as bad omens concerning the Emperor's rule and could even lead to political instability. Modern claims that the IX have been rediscovered, could in fact be a different Legion with the same number ( the practice of different Legions sharing a number is not unknown to historians - the distinctiveness of each legion was in their honouree name e.g. Hispana ). The disappearance of the Ninth Legion is one of the mysteries of the Roman Empire, a mystery that continues to this day - and the finger of suspicion points firmly at the Picts. Several scholars believe that it would have taken a major catastrophic event to cause the emperor Hadrian to decide to build his famous wall in modern England; they argue that the catastrophe was the annihilation of the IX legion by the Picts. One last fact is interesting. An inscription discovered in Rome and dated between 161 AD - 180 AD, lists 28 legions in west to east order - the IX Hispana are absent from the list. Although Tacitus does not mention Caledonia in this next quoted passage, he may have had it in mind, because he is referring to the period just after the invasion of Caledonia when Agricola had been summoned back to Rome. He writes of those days; 'so many of our officers were besieged and captured with so many of our auxiliaries, it was no longer the boundaries of empire and the banks of rivers which were imperilled, but the winter-quarters of our legions and the possession of our territories. And so disaster followed upon disaster, and the entire year was marked by destruction and slaughter.' Note the reference above to the attacks on winter-quarters - this was one of the main strategies of the Picts. Tacitus had earlier written that the Picts, 'had been accustomed often to repair his summer losses by winter successes.' About the time that Tacitus is referring to, Rome retreated from most of their alleged territory of Caledonia. Tacitus makes a ridiculous and unbelievable statement that Caledonia 'was thoroughly subdued and immediately abandoned.' The men of the IX legion and the other Roman officers and legionaries - died for nothing ! |

Build A Wall - No - Two Walls ! |

|

The Emperor Hadrian visited Britain in 122 AD bringing with him a vast number of soldiers, but decided that Caledonia was too much trouble for only a little reward ( yet they had thought it rewarding enough to invade three times ). In a decision designed first and foremost to block the constant punitive raids and daring invasions by the Picts into the Roman provinces, but possibly also ( like the main purpose of the Berlin Wall ), to stop the continual defection of peoples from the occupied territories, he gave orders to the army to abandon Caledonia and to mark and protect the northern boundary of the Roman Empire by building a massive wall the entire width of Britain, near the present border of Scotland and England. The tide had turned, the hunters were now hunted - the Picts had pro-actively seized the offensive. |

Severus |

|

Caledonia was gaining quite a reputation in Rome. In 208 AD ( 128 years after the invasion by Agricola ), 40,000 Romans ( double the force of Agricola ), led personally by Severus - Emperor of Rome, returned to ruthlessly punish the Picts. Not just by war but by destroying their fertile agricultural land. His strategy was simple - ethnic cleansing of all Picts by sword and starvation. In the words of Dr. Colin Martin, Severus policy 'seems to have been nothing short of an attempt at genocide of the Caledonian population'. In actual fact, through giving orders to his 40,000 men to cut down large areas of forest - Severus foolishly created more fertile land. No doubt at the beginning of his campaign he butchered many small helpless villages, killing the elderly, women - even pregnant women and innocent little children, but soon when the Picts learned of his butchery they would have evacuated everyone in his path. |

Scots Dance on Roman Graves |

|

When miners were levelling the ground to build Bridgeness Miners Welfare Club ( to be used for social events and dances ), about 1919, a Roman graveyard was uncovered. When the graves were opened by Officials of the Scottish National Museum, they were found to contain the skeletons of Roman soldiers and numbers of coins and other articles. The coffins being made out of 2 inch thick slabs of stone were too heavy to transport and therefore still lie beneath Bridgeness Miners Welfare Club to this day. I think the Caledonians would have approved. |

"In fact, I think that through the mist I see a forest of spears being shaken and hear the deafening sound of tens of thousands of Brass Apples rattling" |

Legion of the Damned: What caused 6,000 of Rome's fiercest warriors to vanish!! |

|

Over the course of its majestic, turbulent and bloody 1,000-year history, Ancient Rome gave rise to many extraordinary stories which live on to this day. Tales filled with unforgettable, larger-than-life characters who, whether heroes or villains, seem - like Shakespeare's brilliant, but fatally ambitious Caesar - to 'bestride the narrow world like a Colossus, and we petty men walk under his huge legs, and peep about...' No wonder Hollywood has always loved Rome, whose ferocity, passion and sheer spectacle have given rise to great epic movies from Ben-Hur to Gladiator. Yet the latest movies inspired by the barbarous magnificence of the ancient world comes not from the heart of Rome, but from a remote northern province on the edge of the Empire, and an ancient legend that continues to haunt the imagination. A province we now call Scotland, but which the Romans knew as Caledonia. Both films concern the Roman Ninth Legion and the bizarre fate that befell them in the mists of the Scottish Highlands around AD117. The Eagle Of The Ninth will vie with rival project Centurion, starring British actor Dominic West and Bond girl Olga Kurylenko, to do this epic tale justice. For the facts, as far as they can be discerned, are as thrilling as they are peculiar. Like all soldiers, they showed their affection for their great commander by singing obscene songs as they marched along, mocking Caesar's baldness or his notorious and numerous female conquests. Caesar didn't mind. As long as they continued to fight like lions for him, they could sing what they liked. Caesar himself made a couple of fleeting visits to the fog-bound and unknown island of Britain, in 55 and 54BC, claiming them, in an outrageous bit of political spin, as 'conquests'. They were nothing of the sort. It wasn't until AD43, under the Emperor Claudius, that the island was finally brought within the Empire, with the armed might of four entire legions - the IX Hispanica among them. Yet ancient Britain was filled with proud and warlike Celtic tribes, and Rome constantly dreaded rebellion. While Spain and the entire coast of North Africa were kept at peace with a single legion apiece, Britain required three permanent legions. Even so, in AD61, the nightmare came true and much of the island erupted into bloody revolt, under Queen Boudicca. A brutal and corrupt Roman official was to blame. When Boudicca's husband died, the official ordered the seizure of his tribal lands, and had his Queen publicly whipped and her daughters raped for good measure. Such an insult could not be endured. |

|

The flame-haired Boudicca stirred her people to a fury, scorning the Romans under their Emperor Nero as 'slaves to a lyre-player,' and comparing Roman rule of her Iceni tribe to 'hares trying to rule over wolves'. The Queen led her vast tribal army south, striking terror into the hearts of the colonists. She fell upon Colchester and burned it to ground, and then did the same to Verulamium - now St Albans - and London. Even today, when deep foundations are dug in the City of London, the builders invariably encounter a stratum of reddish ash: Boudicca's burning. As many as 70,000 civilians were slaughtered, some in the cruellest ways imaginable. 'They could not wait to cut throats, hang, burn, crucify,' wrote the Roman historian Tacitus.

'In the groves of their terrible dark goddess, Andraste, they tortured their captives to death, sewing the severed breasts of the women to their lips, and impaling others on stakes driven through their bodies. 'No cruelty was too great. When the oppressed rise up against cruel oppressors, restraint is rare.' The first legion to face up to Boudicca was the Ninth. And despite their formidable reputation, in this first conflict they were routed. Massively outnumbered, they lost as many as a third of their number. But their heroism won valuable time for the Governor of Britain, Suetonius Paulinus, to march south from Anglesey, down the Roman road later known as Watling Street - and even later, more prosaically, as the A5 - and meet Boudicca's furious onslaught head-on, somewhere in the flat lands of the East Midlands. Even then Paulinus was outnumbered, his legionaries of 10,000 facing 100,000 howling tribesmen. Yet this would have caused his veterans, the remainder of the Ninth among them, little concern. Odds of ten to one against? The Romans had faced far worse than that before. |

|

They knew that in the end, what won battles wasn't weight of numbers, nor the chaotic onrush of vainglorious painted warriors, but years of weapons training, strict formation, and iron discipline. Sure enough, against the implacable shield wall of Roman legionaries, bristling with those short, squat, brutally effective stabbing swords, wave after wave of tribesmen broke and fell apart. The Iceni were utterly crushed. When Boudicca realised the day was lost, she took poison. But it was also said that, as she lay dying, she put a curse on the legions that had destroyed her people - a curse that people would recall, some 60 years later, in very different circumstances. After Boudicca's rebellion, the Romans slowly and steadily set about subduing the whole island, pushing further north each year. Having conquered the powerful tribe of the Brigantes, the Ninth was stationed at the imposing legionary fortress of York. Sometimes the curtain of history parts and we get a poignant glimpse, and a moving reminder, that these soldiers weren't mere players in a Hollywood movie, but flesh-and-blood people like us. A tiny tombstone was found at York recently, set up by one of those hardbitten, grim-faced legionaries, in memory of his little daughter. It reads: 'To the Gods, the Shades. For Simplicia Forentiana, a Most Innocent Being, Who Lived Ten Months. Her father, Felicius Simplex, made this.' Yet the northern border had still to be pushed back. Beyond York lay the lowland hills of the Borders, and then the Highlands, home of many a ferocious and untamed tribe who were still raiding with impunity down into Roman territory. Caledonia, too, must be 'pacified' for Rome to feel safe. The capable new Governor of Britain, Agricola, led the surge. They called their enemy Picti - the Painted People. The tribesmen of Caledonia were fine specimens of men, with reddish hair and huge limbs. They called themselves 'the last men on earth, the last of the free'. In even the coldest weather they wore nothing but primitive kilts of homespun wool, their bare chests and arms covered in tattoos depicting terrifying emblems of severed heads, shining suns, intertwined serpents and crossed daggers dripping blood. In time of war, though, they painted blood-red stripes across their faces, clad themselves in animal pelts, wolf skins and bear skins, clasped with brooches of red Hibernian gold, and decorated their spears with blue-grey herons' feathers. As they rushed into battle, their shaman priests, called the Druithyn in the ancient Celtic tongue, wearing deer's antlers on their heads, stood on nearby hillsides and raised their arms to heaven to summon the spirits of the dead. They gashed themselves with knives, beat monstrous drums, burnt huge bonfires and howled in fury. The Romans regarded them as nothing but sorcerers - and yet they still evoked fear. Only the strictest discipline and the finest command would prevail against such an enemy. |

|

In AD84 the expeditionary force led by Agricola, including the men of the Ninth, finally met the Caledonian tribes in open battle, under the Picts' own brilliant commander, Calgacus, 'The Swordsman'. The site of the mighty confrontation was called Mons Graupius, somewhere in the wilds of the Cairngorms, and the Roman legionaries were once again savagely triumphant. After the slaughter, records Tacitus: 'A grim silence reigned on every hand, the hills were deserted, only here and there was smoke seen rising - our scouts found no one to encounter them.' It was then Calgacus himself delivered his damning judgment on the whole Roman Imperial enterprise: 'They create a desolation, and they call it peace!' Believing they had taught the rebellious Picts one final lesson, the Romans marched south. But a generation later, fresh rebellion broke out. Which was why, one bleak grey morning in AD117, the 6,000 men of the Ninth Legion tramped north once more. Little did those they left behind, the girlfriends, auxiliaries and townspeople of York, suspect that this would be the last they ever saw of them. Carrying sword and shield and finely-pointed javelin, along with full kit, weighing perhaps 40 or 50lb per man, the legion marched at the steady military pace of 20 miles in five hours. Having marched, they would then set down their kit and build a full camp, every night, including ditches and palisades and gateways, on exactly the same plan as any legionary fortress. For every day a legionary wields a sword, went the saying, he spends a dozen wielding a shovel. Only the very fittest armed forces today could compete with that sort of regime. These were very tough soldiers, indeed. Yet the great loneliness of mountain and moorland and the trackless wild must have weighed on them. They would have glimpsed the occasional wisp of peat smoke, the huddle of turf huts among the gloomy moors, but no more. Their enemy would have eluded them, and they would have had only their meagre rations of bread and bacon and thin soup for comfort, only the endless rain or the first flurries of winter snow for company. And the mist. The mist would have been their worst enemy. For in the mist, the enemy might have closed in on them like wolves as they marched through the lonely glens and begun to harry them, to pick them off one by one. The fear would have begun to grow. Any stray legionaries the tribesmen captured would have been mutilated horribly and left disembowelled, slung over a wayside thornbush for their comrades to find. And there would be worse horrors in store. For there was the defeat of Mons Graupius for the Picts to avenge, and, a generation before that, there was the dying curse of a flamehaired queen called Boudicca...Somewhere out on those godforsaken Scottish moors, death closed in upon the brave, much-honoured IX Legion. Only the faintest rumours ever returned of what had befallen the men - rumours of some terrible battle one winter's day among the heather-clad hills, of an alien army led into some lethal mire. Of the red-crested foreigners fighting to a heroic finale in freezing rain and hail, a last small, wounded band gathered about their silver Eagle totem, fighting to the last man, the motto of every legion on their lips: 'Eagle lost - honour lost; honour lost - all lost.' All we know for certain is that the IX Hispanica disappeared abruptly from the records, an entire legion vanished. A fresh legion, the VI Victrix, was brought over from the Lower Rhine to replace them and stationed at York in AD122. But one visible landmark remains testimony to the Ninth's disappearance. When the new Emperor Hadrian visited Britain soon after, on hearing of the loss of the IX, he commanded a huge wall to be built, a wall studded with fortresses and watch towers, 80 miles from the Solway to the Tyne. We look at Hadrian's Wall today as a splendid monument of Roman power and confidence. But really it was an admission of defeat - and of fear. An entire legion had been eradicated as if at some sorcerer's command. Not a single survivor had stumbled back into camp to tell the tale. There were mysteries and horrors out there in the mists and the mountains of Caledonia which not even the Romans could face again. As in other timeless tales and enigmas that continue to haunt our imaginations, the Ninth Legion simply marched away, beyond our understanding. The tramp, tramp, tramp of those hobnailed boots on the straight Roman roads - and then falling quiet as the roads ended and they set off over the soft heather moorland... They had disappeared from the pages of history - to become legend. |

|

© Paisley Tartan Army 2008-09