JAMES THE GOOD "THE BLACK DOUGLAS" 1286-1330 |

|

| Sir James Douglas (also known as Guid Sir James and the Black Douglas), (1286 – August 25, 1330), was a Scottish soldier and knight who fought in the Scottish Wars of Independence. He was a son of Sir William Douglas, the 'Hardy', who had been a supporter of William Wallace (the elder Douglas died in 1298, a prisoner in the Tower of London). His mother was Elizabeth Stewart, the daughter of Alexander Stewart, 4th High Steward of Scotland. The poet and chronicler John Barbour provides us with a pen portrait of the Black Douglas, among the first of its kind in Scottish history.

|

REBEL WITH A CAUSE |

| James was sent to France for safety in the early days of the Wars of Independence, and was educated in Paris. There he met William Lamberton, Bishop of St. Andrews, who took him as a squire. He returned to Scotland with Lamberton in 1306 to find that his estates had been confiscated by Edward I and awarded to Robert Clifford. Lamberton presented him at court to petition for the return of his land, but when Edward heard whose son he was he grew angry and James had to leave. For James, who now faced life as a landless outcast on the fringes of feudal society, the return of his ancestral estates was to become an overriding consideration, inevitably impacting on his political allegiances. There is no reason to assume that he would not have made his peace with Edward if he had been more receptive, the death of his father in an English jail notwithstanding. But the English king's dogmatic refusal to entertain such a prospect led Douglas to a different path. In John Barbour's rhyming chronicle, The Bruce, as much a paean to the young knight as the hero king, Douglas makes his feelings plain to Lamberton; |

Sir, you see How the English tyrant forcibly Has dispossessed me of my land; And you are made to understand That the earl of Carrick claims to be The rightful king of this country. The English, since he slew that man, Are keen to catch him if they can; And they would seize his lands as well And yet with him I faith would dwell! Now, therefore, if it be your will, With him will I take good or ill. Through him I hope my land to win Despite the Clifford and his kin. |

| This was a particularly dramatic moment in Scottish history: Robert Bruce, earl of Carrick had recently slain John Comyn, a leading Scottish rival, and immediately claimed the crown of Scotland, in defiance of the English king. It was while he was on his way to Scone, the traditional site of Scottish coronations, that he was met by Douglas, riding on a horse borrowed from the bishop. Douglas explained his circumstances and immediately offered his services; |

And thus began their friendship true That no mischance could e'er undo Nor lessen while they were alive. Their friendship more and more would thrive. |

| Douglas was set to share in Bruce's early misfortunes, being present at the defeats at Methven and Dalry. But for both men these setbacks were to provide a valuable lesson in tactics: limitations in both resources and equipment meant that the Scots would always be a disadvantage in conventional Medieval warfare. By the time the war was renewed in the spring of 1307 they had learnt the value of guerilla warfare – known at the time as 'secret war' – using fast moving, lightly equipped and agile forces to maximum effect against an enemy often locked in to static defensive positions. |

Hush ye, hush ye, little pet ye. Hush ye, hush ye, do not fret ye. The Black Douglas shall not get ye. |

|

THE DOUGLAS LARDER |

|

It is important not to make too much of Barbour's magnification of Douglas; for to begin with he was a figure of little real importance. His actions for most of 1307 and early 1308 were local rather than national in nature, confined for the most part to his native Douglasdale. Nevertheless, he was soon to create a formidable reputation for himself as a soldier and a tactician. While Bruce was campaigning in the north against his domestic enemies, Douglas used the cover of Selkirk Forest to mount highly effective mobile attacks against the enemy. He also showed himself to be utterly ruthless, particularly in his relentless attacks on the English garrison in his own Douglas Castle, the most famous of which quickly passed into popular history. Barbour dates this incident to Palm Sunday 1307, which fell on 19 March. This would seem to be far too early, as Bruce and his small army were not yet properly established in south-west Scotland, suggesting Palm Sunday 1308 – 17 April – as a more accurate date. With the help of a local farmer, a former vassal of his father, Douglas and his small troop were hidden until the morning of Palm Sunday, when the garrison left the battlements to attend the local church. Gathering local support he entered the church and the war-cry 'Douglas!' 'Douglas!' went up for the first time. Some of the English soldiers were killed and others taken prisoner. The prisoners were taken to the castle, now largely empty. All the stores were piled together in the cellar; the wine casks burst open and the wood used for fuel. |

| The prisoners were then beheaded and placed on top of the pile, which was set alight. Before departing the wells were poisoned with salt and the carcases of dead horses. The local people soon gave the whole gruesome episode the name of the 'Douglas Larder.' As an example of frightfulness in war it was meant to leave a lasting impression, not least upon the men who came to replace their dead colleagues. Further attacks followed by a man now known to the English as 'The blak Dowglas', a sinister and murderous force "mair fell than wes ony devill in hell." It would seem in this that Douglas was an early practitioner of psychological warfare – as well as guerilla warfare – in his knowledge that fear alone could do much of the work of a successful commander. In August 1308 Douglas met up with the king for a joint attack on the Macdougalls of Lorn, kinsmen of the Comyns, the climax to Bruce's campaign in the north. Two years before the Macdougalls had intercepted and mauled the royal army at the Battle of Dalry. Now they awaited the arrival of their opponents in the narrow Pass of Brander, between Ben Cruachan and Loch Awe in Argyllshire. While Bruce pinned down the enemy in a frontal advance through the pass, Douglas, completely unobserved, led a party of loyal Highlanders further up the mountain, launching a surprise attack from the rear. Soon the Battle of Pass of Brander turned into a rout. Returning south soon after, Douglas joined with Edward Bruce, the king's brother, in a successful assault on the castle of Rutherglen near Glasgow, going on to a further campaign in Galloway |

ROXBURGH FALLS |

| In the years that followed Douglas was given time to perfect his skills as a soldier. Edward II came north with an army in 1310 in fruitless pursuit of an enemy that simply refused to be pinned down. The frustrations this obviously caused are detailed in the Vita Edwardi Secundi, a contemporary English chronicle; The king entered Scotland with his army but not a rebel was to be found...At that time Robert Bruce, who lurked continually in hiding, did them all the injury he could. One day, when some English and Welsh, always ready for plunder, had gone out on a raid, accompanied by many horsemen from the army, Robert Bruce's men, who had been concealed in caves and woodland, made a serious attack on our men...From such ambushes our men suffered heavy losses. For Robert Bruce, knowing himself unequal to the king of England in strength or fortune, decided it would be better to resist our king by secret warfare rather than dispute his right in open battle. Edward was even moved to write to the Pope in impotent fury, complaining that "Robert Bruce and his accomplices, when lately we went into parts of Scotland to repress their rebellion, concealed themselves in secret places after the manner of foxes." In the years before 1314 the English presence in Scotland was reduced to a few significant strongholds. There were both strengths and weaknesses in this. The Scots had no heavy equipment or the means of attacking castles by conventional |

|

| means. However, this inevitably produced a degree of complacency in garrisons provisioned enough to withstand a blockade. In dealing with this problem the Scots responded in the manner of foxes; and among the more cunning of their exploits was Douglas' capture of the powerful fortress at Roxburgh. His tactic, though simple, was brilliantly effective. On the night of 19/20 February 1314 – Shrove Tuesday and Ash Wednesday – several dark shapes were seen beneath the battlements and mistakenly assumed to be cattle. Douglas had ordered his men to cover themselves with their cloaks and crawl towards the castle on their hands and knees. With most of the garrison celebrating just prior to the fast of Lent, scaling hooks with rope ladders attached were thrown up the walls. Taken by complete surprise the defenders were overwhelmed in a short space of time. Roxburgh Castle, among the best in the land, was slighted in accordance with Bruce's policy of denying strongpoints to the enemy. |

BANNOCKBURN |

| The greatest challenge for Bruce came that same year as Edward invaded Scotland with a large army, nominally aimed at the relief of Stirling Castle, but with the real intention of pinning down the foxes. The Scots army – roughly a quarter the size of the enemy force – was poised to the south of Stirling, ready to make a quick withdrawal into the wild country to the west. However, their position, just north of the Bannock Burn, had strong natural advantages, and the king made ready to suspend for a time the guerilla tactics pursued hitherto. On the morning of the 24 June, the day of the main battle, Douglas was made a knight, which seems curiously late in his career. The suggestion that Douglas was 'made a baaneret' (a senior knight with command responsibilities) is a modern invention. Once the English army was defeated Bruce ordered Douglas off in pursuit of the fleeing Edward and his party of knights, a task carried out with such relentless vigour that the fugitives, according to Barbour, "had not even leisure to make water." In the end Edward managed to evade Douglas by taking refuge in Dunbar Castle. Bannockburn effectively ended the English presence in Scotland, with all strongpoints – outwith Berwick – now in Bruce's hands. It did not, however, end the war. Edward had been soundly defeated but he still refused to abandon his claim to Scotland. For Douglas one struggle had ended and another was about to begin. |

WARLORD |

|

Bannockburn left northern England open to attack; and in the years that followed many communities in the area became closely acquainted with the 'Blak Dowglas.' Along with Thomas Randolph, Earl of Moray, Douglas was to make a new name for himself in a war of mobility, which carried Scots raiders as far south as Pontefract and the Humber. But in a real sense this 'war of the borders' belonged uniquely to Douglas, and became the basis for his family's steady ascent to greatness in years to come. War ruined many ancient noble houses; it was the true making of the house of Douglas. The tactics used by Douglas were simple but effective: his men rode into battle – or retreated as the occasion demanded – on small ponies known as hobbins, giving the name of 'hobelar' to both horse and rider. All fighting, however, was on foot. Scottish hobelars were to cause the same degree of panic throughout northern England as the Viking longships of the ninth century. With the king, Moray and Edward Bruce diverted in 1315 to a new theatre of operations in Ireland, Douglas became even more significant as a border fighter. In February 1316 he won a significant engagement at Skaithmuir near Coldstream with a party of horsemen sent out from the garrison of Berwick. The dead included one Raymond de Calhau, seemingly a nephew of Piers Gaveston, the former favourite of Edward II. Douglas reckoned this to be the toughest fight in which he had ever taken part. Further successes followed: another raiding party was intercepted and defeated at Lintalee, to the south of Jedburgh; a third group was defeated near Berwick, where their leader, Robert Neville, known as the 'Peacock of the North', was killed. |

| Such was Douglas' status and reputation that he was made deputy for the kingdom when Bruce and Moray went to Ireland in the autumn of 1316. Douglas' military achievements inevitably increased his political standing still further. When Edward Bruce, the king's brother and designated successor, was killed in Ireland at the Battle of Faughart in the autumn of 1318, Douglas was named as Guardian of the Realm after Randolph if Robert should die without a male heir. This was decided at a parliament held at Scone in December 1318, where it was noted that "Randolph and Sir James took the guardianship upon themselves with the approbation of the whole community." |

MYTON AND BYLAND |

|

In April 1318 Douglas was instrumental in capturing Berwick from the English, the first time the castle and town had been in Scottish hands since 1296. For Edward, seemingly blind to the sufferings of his northern subjects, this was one humiliation too many. A new army was assembled, the largest since 1314, with the intention of recapturing what had become a symbol of English prestige and their last tangible asset in Scotland. Edward arrived at the gates of the town in the summer of 1319, Queen Isabella accompanying him as far as York, where she took up residence. Not willing to risk a direct attack on the enemy Bruce ordered Douglas and Moray on a large diversionary raid into Yorkshire. |

| It would appear that the Scottish commanders had news of the Queen's whereabouts, for the rumour spread that one of the aims of the raid was to take her prisoner. As the Scots approached York she was hurriedly removed from the city, eventually taking refuge in Nottingham. With no troops in the area, William Melton, Archbishop of York, set about organising a home guard, which of necessity included a great number of priests and other minor clerics. The two sides met up at Myton-on-Swale, with inevitable consequences. So many priests, friars and clerics were killed in the Battle of Myton that it became widely known as the 'Chapter of Myton.' It was hardly a passage of any great glory for Douglas but as a tactic the whole Yorkshire raid produced the result intended: there was such dissension among Edward's army that the attempt on Berwick was abandoned. It was to remain in Scottish hands for the next fifteen years. Four years later Edward mounted what was to be his last invasion of Scotland, advancing to the gates of Edinburgh. Bruce had pursued a scorched-earth campaign, denying the enemy essential supplies, so effective that they were forced to retreat by the spur of starvation alone. Once again this provided the signal for a Scottish advance: Bruce, Douglas and Moray crossed the Solway Firth, advancing by rapid stages deep into Yorkshire. Edward and Isabella had taken up residence at Rievaulx Abbey. All that stood between them and the enemy raiders was a force commanded by John de Bretagne, 1st Earl of Richmond, positioned on Scawton Moor, between Rievaulx and Byland Abbey. To dislodge him King Robert used essentially the same tactics as that of Brander in 1308: while Douglas and Moray attacked from the front a party of Highlanders scaled the cliffs on Richmond's flank and attacked from the rear. The Battle of Old Byland turned into a rout, and Edward and his queen were forced into a rapid and undignified exit from Rievaulx, the second time in three years that a Queen of England had taken to her heels |

DOUGLAS! DOUGLAS! |

|

| In 1327 the hapless Edward II was deposed in a coup led by his wife and her lover, Roger Mortimer, Lord Wigmore. He was replaced by Edward III, his teenage son, though all power remained in the hands of Mortimer and Isabella. The new political arrangements in England effectively broke the truce with the former king, arranged some years before. Once again the raids began, with the intention of forcing concessions from the government. By mid-summer Douglas and Moray were ravaging Weardale and the adjacent valleys. On 10 July a large English army, under the nominal command of the young king, left York in a campaign that resembles nothing less than an elephant in pursuit of a hare. The English commanders finally caught sight of their elusive opponents on the southern banks of the River Wear. The Scots were in a good position and declined all attempts to draw them into battle. After a while they left, only to take up an even stronger position at Stanhope Park, a hunting preserve belonging to the bishops of Durham. From here on the night of 4 August Douglas led an assault party across the river in a surprise attack on the sleeping English, later described in a French eye-witness account; The Lord James Douglas took with him about two hundred men-at-arms, and passed the river far off from the host so that he was not perceived: and suddenly he broke into the English host about midnight crying 'Douglas!' 'Douglas!' 'Ye shall all die thieves of England'; and he slew three hundred men, some in their beds and some scarcely ready: and he stroke his horse with spurs, and came to the King's tent, always crying 'Douglas!', and stroke asunder two or three cords of the King's tent. Panic and confusion spread throughout the camp: Edward himself only narrowly escaped capture, his own pastor being killed in his defence. The Battle of Stanhope Park, minor as it was, was a serious humiliation, and after the Scots outflanked their enemy the following night, heading back to the border, Edward is said to have wept in impotent rage. His army retired to York and disbanded. With no other recourse Mortimer and Isabella opened peace negotiations, finally concluded the following year with the Treaty of Northampton, which recognised the Bruce monarchy and the independence of Scotland |

HEARTS AND CROSSES |

|

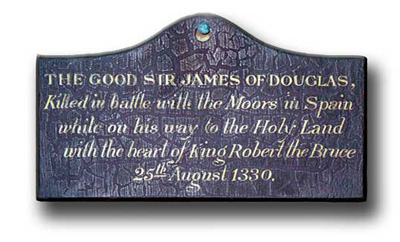

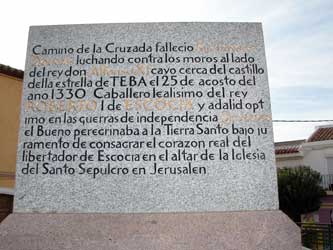

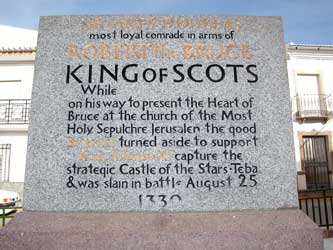

Before he died in 1329, King Robert made it his last request that Sir James, as his oldest and most esteemed companion in arms, should carry his heart to the holy land, and deposit it in the Holy Sepulchre at Jerusalem. His heart was placed in a silver and enameled casket which Douglas placed around his neck. Early in 1330, James Douglas set sail from Scotland with six other knights and twenty six squires and gentlemen. They stopped over first in Sluys in Flanders, where more men joined them. There they received news of a crusade by Alfonso XI of Castile against the Muslims of the kingdom of Granada. Accordingly, they sailed to Seville, where they were received by Alfonso with great distinction. Douglas and his company, having joined themselves to Alfonso's army, came in view of the Saracens near to Teba, a castle on the frontiers of Andalucia. The Moorish king had ordered a body of three thousand cavalry to make a feigned attack on the Spaniards, while, with the great body of his army, he made a circuitous route, unexpectedly, to fall upon the rear of Alfonso's camp. Alfonso, however, having received intelligence, kept the main force of his army in the rear, while he resisted the assault made on the front division of his army. While the battle was brought to a successful conclusion in one quarter of the field, Douglas and his companions, who fought in the van, proved themselves no less fortunate. The Moors, not long able to withstand the furious encounter of their assailants, fled. |

| Douglas, unacquainted with their mode of warfare,followed them until, finding himself almost deserted by his followers, he turned his horse, with the intention of rejoining the main body. Just then, however, he observed a knight of his own company surrounded by a body of Moors who had suddenly rallied. With the few knights who attended him, Douglas turned hastily to attempt rescue. He soon found himself hard pressed by the numbers who thronged upon him. Taking from his neck the silver casket which contained the heart of Bruce, he threw it before him among the enemy, saying, "Now pass thou onward before us, as thou wert wont, and I will follow thee or die." Douglas, and almost all of the men who fought by his side, were here slain. His body and the casket containing the embalmed heart of Bruce were found together upon the field. They were conveyed back to Scotland by his surviving companions. The remains of Douglas were deposited in the family vault at St Bride’s chapel, and the heart of Bruce solemnly interred by Moray, the regent, under the high altar of Melrose Abbey. In 1356 the 'bloody heart' was incorporated in the arms of Sir James' nephew, William, 1st Earl of Douglas. It subsequently appeared, sometimes with a royal crown, in every branch of the Douglas family. |

|

|

Pictures are the copyright of PATRICK HICKEY used with kind permission. |

Click HERE To Read A Wonderful Poem About Douglas |

|

© Paisley Tartan Army 2008-09