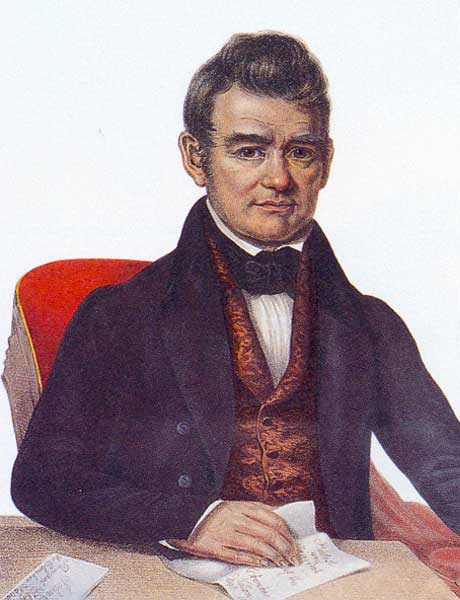

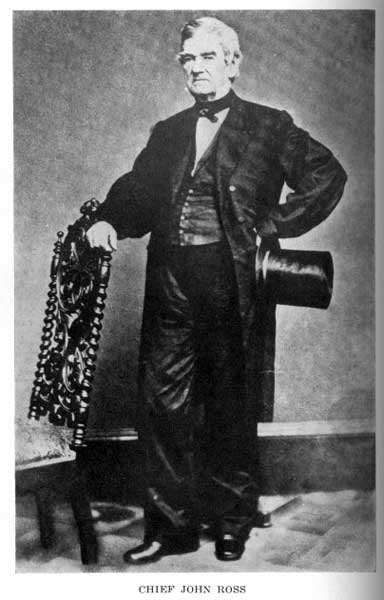

JOHN ROSS CHIEF BRAVEHEART 1790 - 1866 |

|

Hollywood has made us familiar with the names of certain native American chiefs: Sitting Bull, Cochise, Geronimo. All formidable horseback warriors, but the only tribal leader who ever made a real impact on US society was a 19th century Cherokee chief called John Ross. And, as his name suggests, there was hardly a drop of native American blood in his veins, as Ross was one part Cherokee and seven parts Scots. As principal chief of the Cherokee Nation, he was known as “the Indian Prince” in Washington. He haggled with every president from James Madison, in 1816, to Andrew Johnson, in 1866, to keep that nation intact under growing white power. “The great object with me,” he once wrote, “has been to have the Cherokee people harmonious and united in the full and free exercise and enjoyment of all their rights of person and property. Union is strength: dissension is weakness, misery, ruin.” Ross was one of an extraordinary number of Scots who lived and flourished among the powerful Indian nations of America’s southeast. There were Shoreys among the Cherokees, Powells and MacQueens among the Seminole, MacGillivrays and Weatherheads among the Creeks. Just why there were so many Scots among these tribes is still puzzled over. It’s been suggested that there was some natural compatibility between the Scottish clan system and the native tribal |

nations – which were structured quasi-democratically enough to allow even white men into positions of power – but it’s just as likely these relationships grew out of expediency. Every ethnic group in the southeastern states, for example, including French, British and Spanish settlers as well as the native Americans, traded with a particularly influential firm of Scots traders called Panton Leslie & Co (later John Forbes & Co). For decades the firm’s horseback pedlars, almost all Scotsmen, fanned out among the Indians to trade European manufactured goods for skins and furs. These pedlars did good business and for their own safety it made sense to marry a native American woman. Any Scotsman who took a native wife became a full citizen of her nation, and because the Scots understood the white man’s language, politics, law, religion and money, their advice was valuable to the tribes. Many were elected on to tribal councils. Some, like John Ross of the Cherokee, became chiefs. Ross was cast from that trading mould. His grandfather, John Macdonald, was an immigrant from Inverness who did business with the Cherokees and married a mixed-blood girl called Annie Shorey, who was herself the daughter of a Scots merchant and his Cherokee wife. Macdonald’s daughter Molly then married Daniel Ross, an enterprising young Highlander from Sutherland. Their oldest son John was born in 1790. He was raised in the Cherokee nation near what is now Chattanooga, Tennessee, and given a European-style education even while learning the ways of the tribe. He soon came to the notice of the tribal elders and, at the age of 21, was given the dangerous job of making contact with the Cherokees who had drifted west of the Mississippi. In March 1813, a Scots mixed-blood called Billy Weatherford led a rebel army of Creek tribesmen in a massacre of white settlers at Fort Mims in Alabama. Ross was with the 500 Cherokees who joined the avenging army of General Andrew “Old Hickory” Jackson which went on to kill almost all the Creek warriors responsible at Horseshoe Bend. Those bloody events convinced Ross that taking arms against the whites was tantamount to suicide. |

| He returned to his tribe, married a Cherokee girl known as Quatie and became steadily more influential. Fired by the idea of making the Cherokee nation a state unto itself, he moved to modernise tribal society. In 1828, he stood for election as chief and won easily. He was to be re-elected every four years until his death in 1866. There was a worm in the bud, and it was slavery. It pains sentimentalists to learn it, but the Cherokees – like many other native American tribes – owned hundreds of black slaves. There’s no evidence that they treated their slaves any better than white owners – blacks had no status or rights and were freely bought and sold. Interbreeding was brutally punished. Runaways were hunted down. And, exceptional man that he was, Ross kept slaves just like the rest of them. No matter what the Cherokees did to fit into white society it was never enough. In fact it was probably counter-productive. The idea of natives being better organised than whites plainly rankled. The residents of Georgia in particular, seemed to hate the Cherokees with a passion. One governor, Wilson Lumpkin, wrote that “the perplexing evils with which we are embarrassed can only be removed by the entire removal or extermination of the Indian race”. Georgia legislature began to go about this in 1828, by passing an act declaring sovereignty over the Cherokee nation. Ross’s response was to fight law with law – Georgia was flouting the treaties that the Cherokees had signed with the United States. Ross wanted redress and briefed lawyers to take the Cherokee case to the US Supreme Court. That case has gone down in legal history as Cherokee nation vs Georgia and it remains the basis of all US legislation affecting native Americans. The justices decided that the Cherokees (and all other native Americans) were “domestic dependent nations” with a relationship to the US that “resembles that of a ward to his guardian”. Ross won another case at the Supreme Court the following year, which concluded that Georgia had no right to impose its laws on the Cherokees. But, for the only time in US history, a president refused to accept a Supreme Court ruling – and that president was the same Andrew Jackson who had slaughtered the Creeks at Horseshoe Bend. In 1830, Jackson’s administration passed the shameful Indian Removal Act to drive all the tribal nations west of the Mississippi to “Indian Territory”, now Oklahoma. |

| For the next eight years, Ross waged a desperate campaign to keep the Cherokees on their ancestral homelands. But a tiny minority of Cherokees were manipulated by US agents into signing the Treaty of New Echota, in December 1835, which signed away Cherokee lands east of the Mississippi for a paltry $5 million. That sham treaty was the legal gloss that the US government needed to rid itself of the stubborn and resourceful Cherokees. In May 1838, General Winfield Scott (whose grandfather had fought with the Jacobites at Culloden) was ordered to escort the Cherokees to the west with 7000 troops. The natives were herded into stockades and held in terrible conditions to await transport. Hundreds were separated from their families and died beside the Tennessee river. The majority of the Cherokees were driven west in the winter of 1838-39 in parties of 1000 under military escort. Along the way they were preyed on and fleeced by merchants, gamblers, whisky pedlars and thieves. Many of the women were raped. The Cherokees still know that terrible exodus as The Trail Of Tears. They remember it in the same way that Highlanders remember the clearances. Ross and his family were among the many who made the journey by river boat. The vessels were so crowded that disease ran riot. Rations were scant and drinking water polluted, and among the many fatalities was Ross’s wife Quatie who died at Little Rock, Arkansas (her grave is now something of a shrine for surviving Cherokees). It’s estimated that around 4000 – a quarter of the nation – perished before reaching Indian Territory. One Georgia soldier who had done escort duty wrote: “I fought through the civil war and have seen men shot to pieces and slaughtered by the thousands, but the Cherokee removal was the cruellest piece of work I ever knew.” |

|

| Ross set about the task of rebuilding the nation in the Indian Territory, a task complicated by the bitterness felt towards the men who’d signed the Treaty of New Echota, which sparked a violent feud with Stand Watie, the half-brother of a murdered treaty-signatory, that lasted for years. Even so, he formed a new community around the town of Tahlequah, which incorporated schools, hotels, a council house, a court room, a gaol and a newspaper. Tahlequah became known as the Athens Of The Frontier. Ross’s personal life took a turn for the better when he married Mary Bryant Stapler, a Quaker woman 35 years his junior. They settled down in Rose Cottage, a large mansion house stuffed with expensive furniture surrounded by orchards and vegetable gardens worked by Ross’s slaves. |

| Interestingly, this Cherokee grandee never forgot his Scots ancestry. In the mid-1840s when the Highlands were blighted by the potato famine, Ross wrote to the Cherokee Advocate in April 1847 pointing out that many Scots were facing starvation. “Have the Scotch no claim upon the Cherokees?” he asked. “Have they not a very especial claim?” To raise cash, a public meeting in Tahlequah was organised at the beginning of May and nearly $200 was dispatched across the Atlantic to feed Scotland’s poor. The golden age of the Cherokees was brought to an end by the civil war when the nation split in two. Ross’s old enemy Stand Watie became a Confederate general while Ross and his family contrived to be “captured” by Union troops and moved to Philadelphia. Ross spent the rest of the war trying to convince President Abraham Lincoln that the Cherokees had been coerced into the Confederacy and that most were now fighting in blue uniforms. Indeed, four of Ross’s sons fought for the Union and one of them – James Macdonald Ross – died in a Confederate prison camp. His wife died in Philadelphia at the age of 39. And his vacated home, Rose Cottage, was burned to the ground as Watie and his men laid waste to the Cherokee nation. One historian has calculated that no population, north or south, suffered more from the war than the Cherokees. After the war, Ross, then aged 75, fought his last battle – to keep the Cherokee nation together. Watie and his supporters wanted it split in two – a plan that had the support of some powerful (and probably corrupt) members of President Andrew Johnson’s administration. Ross felt that a split would be disastrous and from his sick bed in a Washington hotel, petitioned Johnson, Congress and the press. And in the end, Ross prevailed. Johnson was a more sympathetic man than former president Jackson and was taken with the old chief’s sincerity. Watie was sidelined. On July 27, 1866, Ross signed a new treaty with the US which kept the Cherokee nation together. Four days later, he died. His remains were claimed by the Cherokee nation and his body ended up in the little cemetery not far from the ruins of Rose Cottage. It is due largely to the Scotsman’s tenacity that the Cherokee nation is still based in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, and is now the second largest and probably best-organised tribe in the US. Modern Cherokees acknowledge their debt. “Our greatest chief,” is the opinion of his descendant, the Cherokee writer Gayle Ross. |

|

History of the CHEROKEE |

|

© Paisley Tartan Army 2008-09