|

||||||||

|

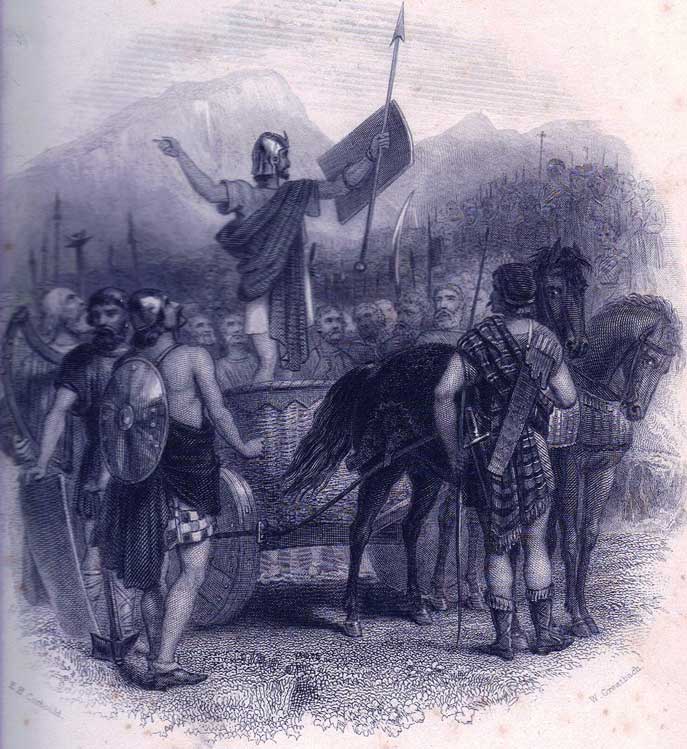

The Romans, under Agricola, had marched into Northern Britain in order to quell the ‘rebellious’ tribes who lived there. It was just before the onset of winter. At a place called by the Romans Mons Graupius, (thought to be near Bennachie in Aberdeenshire, or possibly Duncrub in the County of Perth, though there have been many other feasible suggestions), they were met by a huge and resolute army of angry Caledonian patriots, determined to halt any further Roman incursions into their homeland. The battle and its sorry outcome for the brave but sorely defeated Pictish host was well documented by the Roman historian Tacitus. He was, as it happens, Agricola’s son in law, and writing in around 97 A.D. about Agricola’s campaigns, i.e. only 14 years after the battle, Tacitus also gave us what was supposed to be Calgacus’ rousing speech before the conflict. It is claimed that Tacitus could not possibly have known what Calgacus said to his troops, yet one particular phrase from the speech has a genuine ‘feel’ about it, as if Tacitus had heard it himself from the lips of captured Pictish warriors, and was moved to record it for posterity. It may possibly be described as a romantic view, but we can probably picture Calgacus, described by Tacitus as ‘A man of outstanding courage and lofty noble lineage’, standing on a hillside and looking at the distant smoke of burning villages recently fallen under the ‘protection’ of the Pax Romana. He shakes his head, turns to his captains and says, almost under his breath, that unforgettable phrase: “They create a wilderness and they call it peace.”Take a walk through any deserted Highland glen today and reflect upon those words. When you see the abandoned croft houses disappearing under bracken and heather you should feel the blood boiling in your veins if you are any kind of Scot at all. Tacitus’ account tells us that 10,000 Caledonians lost their lives fighting for their country’s independence in that dreadful battle. It is almost incomprehensible to conceive that all but two thousand long highland winters have passed since that day and that Calgacus’ words are still coming true. As for Calgacus himself we have no more information. He seems to have just disappeared from the pages of history. We can safely say however, that he wasn’t killed on the battlefield, for his death would have been reported. Nor did the Romans capture him, as they would certainly have taken him back to Rome in chains and paraded him as a prize trophy in front of the Senate. This was the Roman way of doing things and this was exactly what they had done with Vercingetorix, the leader of the Gauls, after his defeat at Alesia in 52 B.C. It is likely that Calgacus simply went to ground and became a guerrilla fighter, striking at the invaders of his country whenever he had a chance, and was similar in many ways to that other great Scottish patriot, William Wallace, who suffered his own ‘Mons Graupius’ over twelve hundred years later at Falkirk. Vercingetorix, incidentally, was kept in a cell for six years before being unceremoniously throttled to death. One small extra piece of information has come down to us regarding this battle. It is the kind of snippet that makes you realise that actual mortal men were involved in these wars and that they were more than mere numbers in a list of historic conflicts. From Roman Army records we have the name of an ‘Auxiliary’ (i.e. foreign soldier, serving as a professional) who is recorded as having been wounded at Mons Graupius and had to go to a field hospital after the battle to have his injuries treated. He was a ‘Nervian’ (Belgian), serving, it is believed, with the Ninth Legion, and his adopted Roman name (for you had to drop your own name if you wanted to get on in the Roman Army) was Marcus Aemilius. Recorded as having also fought in the Dacian campaigns (Romania), Marcus eventually retired with an army pension and settled down in a farm in Hungary where he died some years later and was laid to rest with his sword. Quite fitting for an old soldier who had ‘done his bit.’ It feels as if we knew him. We practically admire him, and it’s almost a pity that he was our enemy. Yet enemy he was, for Marcus Aemilius was a soldier in the Roman Army, and through guilt by association with the bitter experiences of people in invaded countries throughout the known world in the first century A.D. that made him a merciless professional killer; a contemptible mercenary who spared neither woman nor child in the relentless and bloody expansion of the Roman Empire. This man may actually have cast his eyes upon Calgacus during the battle of Mons Graupius. He would have heard the bellowing roar of the boar headed Carnyx, (the fearsome war trumpet of the Picts), and ducked as volleys of arrows whistled over his head, finding slower moving targets behind him. He would have gritted his teeth as the Caledonian war chariots with their yelling spear-throwing riders charged remorselessly towards him and would have felt the ground tremble under his feet as the two massive armies crashed together in a chaotic tangle of 60,000 angry and frightened men. Given those formidable numbers this suggestion could hardly be considered likely, but it is just, just, possible that it was Calgacus himself who inflicted Marcus’ wounds. Now don’t you think that is quite an interesting concept? No one today knows the whereabouts of Calgacus’ final resting-place. There doesn’t even appear to be a modern stone raised anywhere to his memory. Surely this man, one of Scotland’s most patriotic sons, deserves better than this opaque oblivion. Even a simple cairn or boulder with his name inscribed upon it would serve. No self-respecting nation would do less would they? As the Romans themselves would have said of him: “Sit tibi terra levis.” |

|

REX PICTORUM |

Back to Top

Return to Paisley T. A. website

© Ron Henderson 2008-09